Our

Impact

OUR IMPACT

We are a nonpartisan political organization that encourages informed and active participation in government. We work to increase understanding of major public policy issues influenced through education and advocacy. We empower New Yorkers to raise their voices for the betterment of their communities.

1,000+

NYC Volunteers

26

meetings held in 2022 with NYS Assembly and Senate legislators

5,000+

voters reached in 2022 at Get Out the Vote events

200+

trained in 2022 on how to conduct voter registration events throughout NYC

52,000+

reached with Civics Education on-line and in-person courses

770

attend monthly current events lectures featuring experts on critical topics

issues & committees

Board of Elections

Elections Specialist: Kate Doran

Kate Doran attends the weekly meetings of the Commissioners of the NYC Board of Elections. Kate prepares and delivers testimony to the NYC Council and the NYS legislature on election/voter related matters. She works with the state League’s Elections Specialist in Albany and with a NYC coalition of nonprofit, good government groups to improve election administration and push for reforms in accordance with LWV positions.

City Affairs Committee

Chairs: Tavonia Davis and Susie Gomes

The focus of the City Affairs Committee is based on our tagline, “Vote Louder” because we believe that your voice is loudest locally. After a hiatus of several years, we reestablished the City Affairs Committee to actively monitor the business of the City Council, the heart of our city’s legislative activities, and to make sure our voices are raised and heard on those issues that are most important to – and aligned with League positions on issues.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Communications Committee

Chair: Stacey Lesser

The goal of the Communications Committee is to ensure that all our constituencies – our volunteers, our members, our donors, as well as the general public – are up-to-date on the activities of the League. This involves publication of a Quarterly Newsletter highlighting the efforts of the various committees, as well as the special events we’re involved in; reaching out to the press to whenever we have noteworthy events and generally keeping our name in the public view. Going forward we will be focusing on helping New Yorkers understand our mission and the efforts we’re taking to achieve it in hopes of motivating them to join us.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Criminal Justice Reform Committee

Chair: Lindsey Reynolds

Advocating for individuals vulnerable to the criminal justice system and legislation and policies to improve the system, in 2024, we focused our efforts on two projects:

The Returning Citizen Project: Workshops designed for formerly incarcerated persons to encourage them to vote and become involved in their communities.

Vote in NYC Jails Coalition: Through this coalition of legal service providers and community-based organizations League volunteers visited detainees at Riker’s to help register voters, access absentee ballots and provide ballot information.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Committee

Chairs: Sherletta McCaskill and Talia Miele

The vision of the DEI Committee is to provide tools and open forums for discussion within the League so that it will comprehensively conduct its work – both internal and external – with an eye towards diversity, equity and inclusion. We believe such introspection and openness are important for us to truly represent the city we serve; reflect the racial, ethnic, geographic, socioeconomic and ability status of our constituents; and empower all of our voices and representation concerning voting rights and civic engagement.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Education Committee

Chair: Jane Hatterer

We advocate for New York City and State policies and programs that support equal access to a sound basic education and to provide resources for Civic Education.

From the founding of the United States, a primary purpose of education has been to prepare individuals to become capable citizens. For almost 100 years, the League of Women Voters of New York City has supported equal access to education so that students are prepared to become informed and contributing citizens who understand their rights and responsibilities.

To that end we:

- Support a greater emphasis on Civic Education in the curriculum*

- Support funding for Universal Pre-K

- Support the Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) demands that NY State provide adequate funding for high needs school districts

- Oppose State tax credits for donors to private and parochial schools

- Oppose school vouchers

- Support at least a 3-year extension of Mayoral control of NYC public schools to enable the Department of Education to engage in long-term planning

- Support inclusion of the Department of Education’s governance responsibilities in the New York City Charter as is done with every other city department

We are currently working on a proposal for Professional Development for NYC Social Studies teachers in the area of Civics Education.

Join us to work on these and other issues related to public education in New York City.

*Teaching High School Students How to Engage in Politics: The state League and the NYS Social Studies Supervisory Association (NYS4A) are pleased to announce the publication of seven lesson plans on state and local government for teachers of the New York Grade 12 Participation in Government course. Please see Topics and Lesson Plans here.

We usually meet on the second Wednesday of the month at 5:30 PM. Check our website calendar for meeting dates. For more information, please contact [email protected]

Housing Committee

Interim Chair: Kai Rosenthal

The Housing Committee advocates for social change, may determine new, positive housing initiatives and highlight existing successful policies and programs. The League has long held the position that government should have policies that assure an adequate supply of decent affordable housing in New York City, support an expansion of zoning when addressing affordable housing and support increased density provided that developments ensure there is adequate infrastructure. We will also take positions on particular housing proposals, join appropriate coalitions and possibly support local legislation.

If you have experience in the housing space or an interest in the issue, we hope that you will join the LWVNYC Housing Committee. For more information, contact [email protected]

Membership Committee

Members and volunteers are the heart of The League. We welcome volunteers at all levels of participation: Want to register voters on a weekend, dedicate time to policy work, or help lead civic engagement events? Please reach out! Those who join as dues-paying members also become a part of the State and National League of Women Voters, which pursue voting rights and other critical issues on a larger scale. Members are also eligible to represent the League when visiting with elected officials or speaking to community groups and can vote at the League’s annual meeting.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Next Gen Committee

NextGen is a new committee organized to increase awareness of age, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status in our League’s advocacy efforts. Through the lens of Millennials and Gen Z, we will bring lived experience to focus on creating events and projects designed to address national and local issues, and NYers’ ability to “do” something about them.

For more information, check out the Next Gen site, or contact [email protected].

Program Committee

Chair: Joanna Leefer

Join us if you’re interested in planning events that educate people about public policy issues. We meet on the first Monday of the month; join us at either 10:30am or 6pm. The Chair meets twice to accommodate committee members who prefer daytime meetings and those who prefer evenings.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Transportation Committee

Chair: Sarah Erdos and Michael Price

The Transportation Committee supports action to promote sustainable, equitable, and accessible transportation systems in New York City. Transportation is the lifeblood of the city and through coalition building, advocacy, and policy change, the Committee aims to help New Yorkers benefit from a more efficient and safe system that is essential to their daily routines.

For more information, please contact [email protected]

Voter & Information Services Committee

Co-Chairs: Diane Burrows and Tara Pehush

The Voter & Information Services Committee conducts voter registration drives throughout the five boroughs, trains organizations and individuals on how to conduct voter registration drives, and provides speakers to organizations and schools about why voting is important and what to expect on the ballot.

The Volunteers who staff our Telephone Information Service provide callers with vital voting information and related matters. We also have a Committee member who is an observer at the NYC Board of Elections Commissioners’ weekly meetings. This volunteer advocates to improve election laws, simplify and modernize the registration and the voting process.

If you’d like to join this committee, all are welcome. We currently have three work groups addressing: Voter Registration Events, Voter Registration Volunteers, and Get Out The Vote. Click here for calendar of next meeting date as well as training dates.

To volunteer to help staff one of the many Voter Registration Drives, please complete this form.

Voting Reform

Chair: Bella Wang

The Voting Reform Initiative advocates on issues relating to elections in New York City and New York State, through activities such as meetings with legislators, op-ed writing, and voter education and activation projects. We are currently focused on the following issues:

- Same-day voter registration and no-excuse absentee voting

- Full restoration of voting rights and voter access in jail

- Board of Elections reform

To stay updated on our activities, email [email protected] to sign up for our mailing list.

diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) at the league

The League of Women Voters is an organization fully committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion in principle and in practice. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are central to the organization’s current and future success in engaging all individuals, households, communities, and policy makers in creating a more perfect democracy.

Diversity – means that participants in an organization reflect the community that they want to serve.

Equity – is to go a step further and give those participants an equal opportunity to be in leadership, to have their voices heard and to advance the organization.

Inclusion – means that all voices are heard when they speak up, comment, or make suggestions, and are made to feel and actually

are included.

The LWVNYC DEI Committee welcomes all participants and input. Our role is to help assure that we engage in all League functions, both internal and external, “through a DEI lens”.

More information on the DEI Committee is available here.

“Even during the Civil Rights movement, the League was not as present as we should have been. While activists risked life and limb to register black voters in the South, the League’s work and our leaders were late in joining to help protect all voters at the polls. It wasn’t until 1966 that we reached our first position to combat discrimination. Still, our focus on social policy was from afar—not on the front lines.

Today, we acknowledge this shortcoming and that we have more work to do.

The League of Women Voters serves millions of voters in underrepresented communities across America every year, but as an organization, our membership does not always reflect the communities we serve. As we approach our 100th anniversary, we are not only striving for better, we will do better.”

Click Here To View Full Statement“The path to women’s suffrage was complicated, and sometimes ugly. History books tend mostly to credit the courage and tenacity of white women. It is past time to amend the history books and tell the real story of the suffrage movement.

…It is past time we all celebrate the women of color…

who were at the center of the movement alongside their white counterparts. And it is past time for our country to acknowledge that when the 19th Amendment was ratified, many women still weren’t able to cast a ballot because of Jim Crow laws that denied them full enfranchisement.”

Click Here To View Full Statementerased suffragist project

The League of Women Voters of the City of New York has begun a project to lift up women who were erased from the history of women’s suffrage, primarily women of color. We will be publishing and maintaining research on them for all interested in learning more about these brave women who fought for suffrage for all people.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer

Contributed by Sherletta McCaskill

Voting rights activist, community organizer, and leader in the Civil Rights Movement, Fannie Lou Hamer was born on October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi, the youngest of twenty children born to sharecroppers. She grew up working in the cotton fields and left school at a young age to help support her family. Years later, when she attempted to register to vote in 1962, she was fired from her job and forced off the plantation where she had lived and worked for nearly two decades.

That moment changed the course of her life. Hamer began organizing Black voters across Mississippi, despite threats, arrest, and violence. In 1963, she was brutally beaten while jailed for attempting to desegregate a bus terminal. The assault left her with lifelong injuries, but it did not silence her.

As Vice Chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Hamer traveled to the 1964 Democratic National Convention and delivered a nationally televised testimony detailing the violence and intimidation used to prevent Black citizens from voting. Her words exposed the realities of voter suppression to millions of Americans.

Hamer later co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus to recruit and support women of all races seeking public office. Throughout her life, she insisted that political power must include those who had long been excluded. She died on March 14, 1977. Her legacy lives on in every effort to expand and protect the right to vote.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Contributed by Tania Padgett and Romon Mckenzie, Color of Justice

Journalist, educator and activist, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, just six months before the Emancipation Proclamation. She would go on to become one of the most powerful leaders in early 19th century civil rights and suffragist movements. Wells-Barnett was educated at a historically Black college until tragedy struck in 1878 when both her parents and infant brother succumbed to yellow fever. She was just 16 but managed to take care of her siblings while making money as a teacher. She continued her education at Fisk University where she spoke passionately on racial injustice and women’s rights. During this time, her journalism flourished. When her dear friend Thomas Henry Moss was lynched, Wells-Barnett set out to investigate why African-American men were increasingly being targeted by this violence; she published her extensive findings in a pamphlet and wrote scathing anti-lynching columns for several Black newspapers. One such column enraged white people so much that a mob attacked and destroyed the offices of newspaper she wrote for and co-owned in 1892. That and threats against her life forced her to flee Memphis for Chicago. In 1895, she married prominent Chicagoan attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett, and they had four children. Wells-Barnett’s activism soon turned to women’s suffrage. She helped start the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and the Alpha Suffrage Club in 1913, which both focused on getting women the vote. Wells-Barnett frequently pushed back against the racism within the women’s suffrage movement. When she was asked to march in the back of a prominent women’s suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., in 1913, she refused and walked with the white Illinois delegation. Wells-Barnett began writing her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, in 1928, but never completed it. She died in Chicago on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68.

Mary Church Terrell

Contributed by Tania Padgett and Romon Mckenzie, Color of Justice

Mary Church Terrell was born on September 23, 1863, in Memphis, Tennessee. A renowned educator and speaker, she fought for women’s suffrage and equality for African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century. She was born into privilege as her father, Robert Reed Church was a well-regarded businessman, and one of the first African-American millionaires in the South. Her mother Louisa Ayres Church owned a successful hair salon. Terrell earned her bachelor’s from Antioch College laboratory school in Ohio and her master’s degrees from Oberlin College. She went on to become a teacher. Her hunger for activism began in 1892 when her old friend Thomas Moss was lynched in Memphis because his business was competing with a white-owned grocery. Terrell immediately joined anti-lynching campaigns, but her main goal was racial upliftment by ending racial discrimination and advancing African Americans through education, work and activism. She co-founded the National Association of Colored Women, where her phrase “lifting as we climb” became the organization’s motto. Terrell also served as its president from 1896 to 1901. By 1909, she had become one of the founders and charter members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, then co-founded the National Association of University Women in 1910. In 1913, she participated in a demonstration outside of the Woodrow Wilson White House with the National American Women Suffrage Association but was appalled when leaders of the group asked Black suffragists to march in the back. She and others refused to do this and integrated the march. In 1940, Terrell published her autobiography A Colored Woman in a White World, where she discussed her civil rights activism, the suffrage movement and the racism within it. She continued to fight for racial equality well into her 80s. In 1950, when she was 86, she fought to have restaurants desegregated in the District of Columbia. Her actions prevailed. Three years later, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated eating facilities were unconstitutional. Terrell passed away July 24, 1954. She was 90.

Frances Watkins Harper

Contributed by Anna Bamber

One suffragist whose contributions have been largely overlooked in history is Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Frances Harper was an African American poet, author, and abolitionist who also played a significant role in the suffrage movement. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Harper was orphaned at a young age and raised by her aunt and uncle. Harper’s advocacy for women’s suffrage began in the 1860s when she joined various suffrage organizations, including the American Woman Suffrage Association and the American Equal Rights Association. She delivered powerful speeches at national conventions, using her voice to highlight the intersectionality of race and gender. In 1866, Harper delivered a powerful speech titled “We Are All Bound Up Together” at the National Women’s Rights Convention in New York. In her speech, she emphasized the importance of including African American women in the suffrage movement and the need for solidarity among women of different races. Harper’s poignant words called for unity and equality among all women, challenging the predominantly white suffrage movement to recognize and address racial discrimination. Despite her influential contributions, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s name and achievements have often been overshadowed by other figures of the suffrage movement. The erasure of African American women’s voices from historical narratives has led to an incomplete understanding of the suffrage movement’s diversity and intersectionality.

Queer Women Suffragists

Contributed by Anna Bamber

Queer women suffragists played a crucial role in the fight for women’s right to vote during the suffrage movement. Many histories of the movement omit the stories of their lives and contributions due to social stigmas and the erasure of queer identities. However, there are many notable individuals whose stories deserve to be told. Following are the biographies of a few prominent queer women suffragists. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw (1847-1919), at right, was a renowned suffragist and an openly lesbian woman. She became involved in the women’s suffrage movement in the United States and eventually served as the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1904 to 1915. Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) was an African American writer, suffragist, and educator. While her sexual orientation is not as extensively documented, she had relationships with both men and women, suggesting her queer identity. Dunbar-Nelson was involved in various suffrage organizations and used her platform to fight for gender and racial equality. Mabel Hampton (1902-1989) was a Black lesbian activist who actively participated in the women’s suffrage movement. She joined the Harlem branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and fought for civil rights and women’s suffrage throughout her life. Hampton’s activism continued beyond the suffrage movement, advocating for LGBTQ+ rights in later years. Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919) was a physician, abolitionist, and women’s rights advocate. While her sexual orientation is not as widely discussed, there is evidence to suggest that she had same-sex relationships. Dr. Walker actively participated in the women’s suffrage and was awarded the Medal of Honor for her medical services during the American Civil War. These are just a few examples of queer women suffragists who made significant contributions to the fight for women’s right to vote. It’s important to acknowledge and honor their often overlooked and marginalized roles in the suffrage movement, as their experiences shed light on the diverse backgrounds and identities of those involved in this pivotal moment in our country’s history.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935)

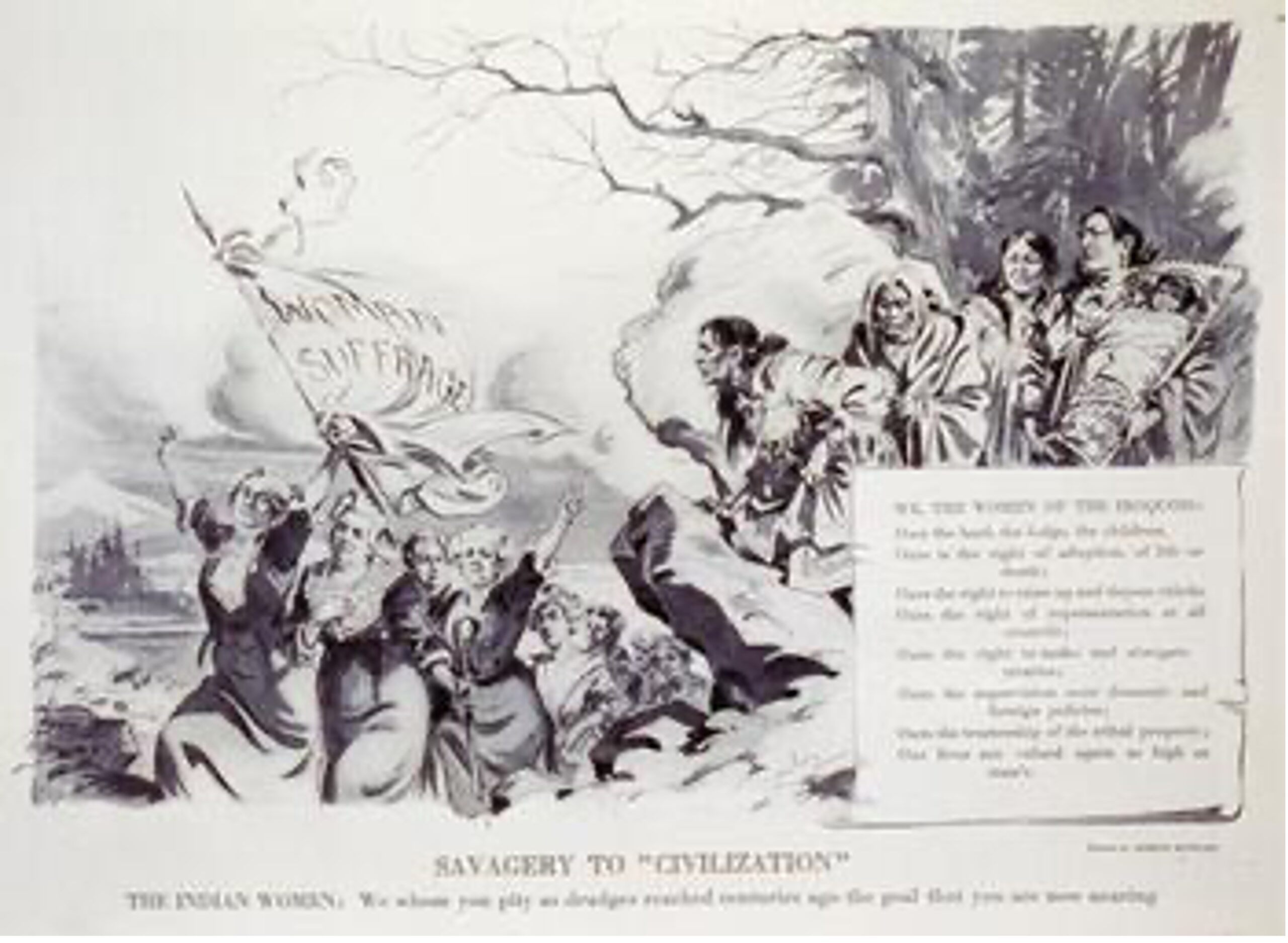

The Haudenosaunee Women of New York

Contributed by Anna Bamber

The Haudenosaunee tribe, which inhabited New York State long before European settlers’ arrival in America, has long valued women’s involvement in political leadership at times when women still did not have a voice in the American government. The early suffrage movement that took place in New York in the 19th century was, in fact, inspired by the native communities surrounding them. The matrilineal nature of this tribe made it so that a “clan mother” was in charge of the community and had the authority to regulate threatening men in their society. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a White pioneer of the suffrage movement, made several remarks about the Haudenosaunee tribe’s female-oriented power structures in her 1891 speech to the National Council of Women. She was impressed by the divorce proceedings in this community; by which women had the power to kick their husbands out of the house in the event that a divorce occurred. (Buffalo Times). This clearly departed from the dominant Christian tradition of marriage that many women endured in this time period. Once married, the woman was property of her husband and since she did not have legal independence, she was reliant on the husband to stay alive. The safety that women could feel in their communities without threat of domestic violence was also a key trait of the Haudenosaunee that suffragettes marveled at. The political leadership positions that women in the tribe held as well as the autonomy they had over their marriages, children, and bodies provided inspiration to suffragettes to imagine a country where men and women were treated equally. The influence that the Haudenosaunee tribe had on the suffrage movement and on pioneers like Elizabeth Cady Stanton was invaluable in the fight for gender equality and women’s right to vote.

At the top of this entry is a cartoon by Joseph Keppler, entitled Savagery to Civilization, originally published on May 16, 1914, depicting the Haudenosaunee women watching the women’s suffrage movement with a banner scroll reading: “We, the women of the Iroquois: Own the land, the lodge, the children. Ours is the right of adoption, of life or death; Ours is right to raise up and depose chiefs; Ours the right of representation at all councils; our the right to make and abrogate treaties; Ours the supervision over domestic and foreign policies; Ours the trusteeship of the tribal property; Our lives are valued again as high as man’s. THE INDIAN WOMEN: We whom you pity as drudges reached centuries ago the goal that you are now nearing.” (https://nyheritage.org/exhibits/recognizing-womens-right-vote-new-york-state/haudenosaunee)

Charlotte Forten Grimké

Contributed by Leanne Daley

Charlotte Forten Grimké was brought up in a well-off prominent Black family from Philadelphia. Her grandfather was of fourth-generation African descent and became one of the wealthiest men of African descent after an apprenticeship under a sailmaker led to him taking over the business. They used this financial success to buy slaves freedom as well as fund the Underground Railroad. Her mother died when she was three, and her aunts and grandmothers stepped in to fill the role of a mother. Her father remarried and she lived with them until her father decided that he wanted her to be educated in integrated schools. By using family connections she was sent to live in Salem, Massachusetts with the Remond Family where, before the Civil War, there was a lively African American community learning in integrated schools. She graduated with the class of 1856 from Salem State and was the University’s first African American graduate. She was working to carry out her father’s wishes of becoming a teacher, and wrote that her school days in Salem were, “the happiest of my life….I have been fortunate enough to receive the instruction of the best and kindest teachers; and the few friends I have made are warm and true—New England”. By working through school she was able to secure a teacher position and became the first African American teacher in Salem public schools.

Throughout her education and life, Charlotte faced challenges due to both her gender and race, but she turned to writing as a way to express her anger and advocate for solutions. She moved to Sea Islands in South Carolina as part of an effort to educate the previously enslaved people on abandoned plantations. Although she left after the death of her father, she wrote a two-part essay reflecting on her time there, depicting the new citizens as eager to learn, support themselves, and assume the responsibilities of citizenship. Once back in Massachusetts, she served as secretary of the Freedmen’s Union Commission’s Boston branch. Later she returned to teaching at an all-Black school in Washington, D.C., and clerked at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Charlotte married the Reverend Francis Grimké at age 41, and after her marriage, she continued her activism by joining the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and advocating for women’s suffrage. She also continued to write poetry and essays calling for an end to racial injustice and violence. Charlotte’s story is an inspiring one, and she was a trailblazer for African American women in education and activism. Her legacy lives on, and her contributions to the fight for equality and justice will never be forgotten.

Harriet Purvis, Jr.

Contributed by Leanne Daley

Harriet Purvis, Jr. was the daughter of renowned abolitionists and activists for equal rights, Harriet Forten Purvis and Robert Purvis. Known as Hattie, she was involved in abolitionist and women’s rights work from a young age. She grew up in a household that was at the forefront of the abolitionist movement in Pennsylvania and a stop on the Underground Railroad. Her parents were associated with various reformers, including Susan B. Anthony.

Harriet was considered to be part of the second generation of American suffragists. She joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, founded by her grandmother, mother, and aunts in 1866. From 1866 to 1869, she worked with her mother on the anti-slavery fair, aiming to raise funds for its abolitionist activities. She attended the 1866 National Woman’s Rights Convention and became a member of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), where she served as corresponding and recording secretary until the group dissolved in 1869. Harriet also joined the Pennsylvania Woman’s Suffrage Association, where she served on the executive committee. From 1883 to 1900, she was a delegate to the National Woman’s Suffrage Association and served as its first African-American vice president. She worked closely with Susan B. Anthony to advocate for women’s rights. She was also active in the temperance movement and joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and encouraged Black women to participate in the movement. She was a committed suffragist who never married, and spent her life dedicated to her work.

Margaretta Forten

Contributed by Leanne Daley

Margaretta Forten was born into a prominent family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was the daughter of James Forten, a wealthy sailmaker and prominent abolitionist, and his wife Charlotte Vandine Forten. Margaretta was one of their six children, and education was of utmost importance to Margaretta’s family, and her father worked tirelessly to secure the best possible education for his children. Unfortunately, in an age when schools for black children were scarce and often inadequate, this was not an easy task. However, Margaretta’s father, James Forten worked with Grace Douglass to open a school in 1819. They hired a teacher named Britton E. Chamberlain. When the school was eventually taken over by Sarah Mapps Douglass, Grace’s daughter, Margaretta attended the school while also receiving additional education at home. She learned to speak and read French. Margaretta along with her sisters and mother were all charter members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, which was established in 1833. She remained actively involved in the society for nearly four decades. She served as the recording secretary and treasurer, represented the group at statewide abolitionist meetings, and worked on various committees, including the membership, education, petition campaign, and annual antislavery fair committees.

For more than 30 years, she ran a successful private school, the Lombard Street Primary School, where she served as principal starting in 1845. She was a dedicated teacher, and her influence on her niece, Charlotte Forten Grimké, was profound. Charlotte owed much of her early education to her aunt, and they corresponded frequently while Charlotte was away at school. Sadly, Margaretta suffered from recurrent respiratory problems, possibly from tuberculosis, and had to take absences from school a number of times. Two of her sisters, as well as her nieces and nephews, also suffered from respiratory problems. Despite her health issues, Margaretta remained a dedicated advocate of social reform until her death from pneumonia on January 14, 1875. Margaretta Forten’s dedication to education and social reform changed the lives of countless people and inspired future generations to continue the fight for equality and justice. Her legacy lives on today, and she will always be remembered as a champion of freedom and equality.

Marguerite Rawalt

Contributed by Gilli Richman

Marguerite Rawalt was born on October 16, 1895, in Prairie City, Illinois. Rawalt attended the University of Texas for a year and she then taught high school math. She was a secretary to Texas Governor Pat Neff from 1921 to 1924. She then attended night school at George Washington University Law School and earned her law degree in 1933. After law school, she became an attorney in the office of the Chief Counsel at the Bureau of Internal Revenue (now known as the Internal Revenue Service or IRS). Rawalt lobbied in Congress on behalf of women’s rights. She served as president of the National Association of Women Lawyers and was eventually elected the first woman president of the Federal Bar Association in May 1943. She co-founded the National Organization for Women (NOW) and held the role of its legal counsel.

Marguerite Rawalt became involved with President Kennedy’s Commission on the Status of Women. She actively campaigned for the inclusion of Provision VII in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which aimed to prohibit sex-based discrimination by employers. Rawalt reached out to members of organizations, like Business and Professional Women and Zonta International, urging them to support the passage of this provision. Later, in 1972, she founded the Marguerite Rawalt Legal Defense Fund, which focused on providing financial support for legal cases concerning women’s equality, particularly in the financial realm. After serving with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for thirty years, Rawalt retired from her position in 1965. She was an advocate for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and attended the International Women’s Year Conference in Mexico City in 1975.

Alice Paul

Contributed by Gilli Richman

Although not erased, Alice Paul is a pioneer in the women’s suffrage movement as she advocated for the passage of the 19th Amendment allowing women the right to vote. Additionally, Paul authored the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in 1923, which we are fighting to ratify today.

Alice Paul was born on January 11th, 1885 to wealthy Quaker parents. She attended Swarthmore College in 1905 to study Biology and then the New York School of Philanthropy (now known as Columbia University) to receive a Masters in Sociology in 1907. After studying social work in England, Paul received a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1910.

In 1912, Alice Paul joined the National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and led the Washington DC chapter. She lobbied Congress to create a constitutional amendment and parted from the NAWSA to create the National Woman’s Party. Paul took initiative by leading rallies, parades, and pickets to advocate for women’s suffrage. One of Paul’s greatest accomplishments is known as the Women’s Suffrage Parade in Washington. On March 3, 1913, around 8,000 women gathered to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the White House with banners and floats on the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. Fourteen days later, Paul met with President Wilson to push for women’s right to vote but was told that it was not the right time to introduce women’s suffrage as a new amendment to the Constitution. To counter that idea, Paul founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage which specifically targeted Congress. Paul organized over 1,000 women to protest outside the White House in 1917, for eighteen months, with the goal of gaining elected officials’ attention to create change and allow women the right to vote. She was jailed for seven months because the police arrested women to try and end the picketing. While in jail, Paul organized a hunger strike which gained the media’s attention and garnered further support for the women’s suffrage movement. In 1918, President Wilson declared his support for women’s suffrage and then the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. Paul’s leadership and advocacy inspired thousands of women to join the fight for equality and women’s suffrage.

After women gained the right to vote, Alice Paul, along with the National Women’s Party, worked on the Equal Rights Amendment to guarantee women constitutional protection from discrimination. She was instrumental in the drafting and introduction of the ERA with the hopes of ensuring equality for women in all areas of life. Although the ERA was ratified in 1970, it was three states away from the thirty-eight needed to be added as a constitutional amendment.

Alice Paul made a great impact on women’s history as both an advocate and a leader. She inspired many women to continue in the fight for gender equality and she played a large role in working towards women’s rights internationally, by aiding in the formation of the United Nations. Her trailblazing efforts for gender equality remind us of the importance of being advocates to further equality and justice today.

Sojourner Truth

Contributed by Gilli Richman

Sojourner Truth was born in 1797 with the birth name of Isabella Bomfree. She was a slave in Ulster County, New York where she was bought and sold by slave owners four different times. Growing up, she experienced terrible living conditions, harsh labor, and violent beatings. In 1827, Truth escaped to the Van Wagner family, who were abolitionists, where they bought her freedom for twenty dollars. A year later in 1828, the year that New York’s Anti-Slavery Law was put into effect, Truth moved to New York City. She found work with a local minister where she then became a strong-willed speaker who proclaimed that the Spirit had called on her to preach the truth. Therefore, she renamed herself as Sojourner Truth.

Sojourner Truth met many abolitionists while she preached which led to her giving speeches on the horrors of slavery. Truth dictated her autobiography, titled “The Narrative of Sojourner Truth”, as she had never learned to read or write. She received her livelihood from sales of her book which received significant traction causing Truth to become more widely known. She encountered many women’s rights activists including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She quickly felt drawn to women’s rights issues and started speaking about this topic when giving her lectures. In Akron, Ohio during the Women’s Rights Convention, Truth gave her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech which challenged society’s views about both women and race. Truth faced struggles because some women’s rights groups did not specifically want to be linked to anti-slavery movements. However, Truth continued to advocate for women’s rights and all women’s suffrage.

After settling in Michigan in the 1850s, Truth continued to help slaves escape towards freedom and played a major role in providing supplies and support throughout the Civil War. After the war, Truth met President Abraham Lincoln in 1864 when she was invited to the White House. She assisted with the Freedmen’s Bureau, where she aided slaves’ freedom and assisted in helping them rebuild their lives by finding them jobs and homes. Truth spent decades using her voice, strength, and beliefs to stand up for equality, justice, and civil rights for all.

Anita Lily Pollitzer

Contributed by Gilli Richman

Anita Lily Pollitzer was born in Charleston, South Carolina on October 31, 1894. She was the fourth child of Jewish Eastern European immigrants. After Pollitzer graduated from the School of Practical Arts at the Teachers College at Columbia University in 1916, she marched in the suffrage parade in New York down Fifth Avenue. She made a big decision to move to Washington to work for National Woman’s Party (NWP) shortly after receiving her diploma. Pollitzer became a leader in both the equal rights and suffrage movements. She traveled through various states and organized fundraisers, gave speeches, and even participated in picketing outside the White House during Woodrow Wilson’s administration.

Pollitzer played a crucial role in the ratification of the 19th Amendment by dining with legislator Harry T. Burns the night before he had to vote in a special session of the Tennessee Legislature. As a result, Burns ultimately cast the deciding vote in 1920. Pollitzer continued with her long-lasting work for the NWP. At only 25 years of age, she became the Secretary of the Legislative Committee for the NWP as a result of her success in talking with senators and her various lobbying victories. After her time serving as Secretary, Pollitzer was then elected Vice-Chairman of the NWP from 1927 to 1938. In addition to her fight for the 19th Amendment and women’s suffrage, Pollitzer also put her time and effort into supporting the Equal Rights Amendment into becoming part of the United States Constitution.

Adelina Otero-Warren

Contributed by Gilli Richman

Adelina Otero-Warren was born on October 23, 1881. In 1916, Otero-Warren was elected to head New Mexico’s chapter of the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage, soon to be the National Woman’s Party (NWP). A year later, she took the role of chair of the NWP at the request of Alice Paul. Adelina Otero-Warren was the first female superintendent of public schools until 1929 in Santa Fe and inspector of Indian schools throughout the 1920’s. She advocated for adult education programs, raising teacher salaries, creating a county high school, and elevating the conditions of schools to promote greater education. She fought to protect the study of Hispanic art and wanted to preserve bicultural education. She was the first Hispanic woman to run for the United States Congress in 1922 and won the Republican Party’s nomination while running against a male opponent, although she was defeated in the general election. She served as New Mexico’s Director of Literacy Education for the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. Additionally, she worked with Mamie Meadors in homesteading 1,257 acres of land which they named Las Dos (“The Two Women”). She continued her work into the 1940’s as director of the Works Progress Administration in Puerto Rico. Otero-Warren published a book titled “Old Spain in Our Southwest”, a compilation of stories from her childhood in Los Lunas.

Additionally, she was a leader in New Mexico’s women’s suffrage movement. Otero-Warren saw a need for Spanish-speaking leaders in the suffrage movement because of the large number of Hispanic women who wanted to fight for women’s rights to vote. She knew that gaining the support of the Latinx community was key to victoriously creating suffrage on a national level. Therefore, Otero-Warren was a key force in the lobbying effort to ratify the 19th Amendment in New Mexico. She fought to improve education for New Mexicans and worked to preserve the cultural practices of the state’s Hispanic and Native American communities. She insisted that suffrage literature in the southwest be published in both English and Spanish in order to be inclusive of all and to reach a greater audience that she knew was ready to join the cause. Otero-Warren passed away in 1965 but her impact on women’s suffrage was tremendous within the United States. In 2022, the United States Mint honored her with her portrait on an American Women’s Quarter made to honor the accomplishments of American Women.

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Contributed by Rahima Khatun

“For no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization unless its women are following close to its men, if not actually abreast with them.”

— Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Born in 1896 in Guangzhou, China, Lee moved to New York with her family during the era of the Chinese Exclusion Acts. From 1882 to 1943, these acts aimed to curtail immigration from China through strict immigration requirements; only exceptions were made for groups such as students and missionaries. Her father was a missionary and, thus, was granted this exception. Furthermore, the Chinese Exclusion Acts prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming American citizens, thereby disenfranchising them.

This did not discourage Lee. Influenced by her father’s religious and nationalistic views of China and by New York’s tolerant environment, she began to write and speak publicly about suffrage. In 1912, she led a pro-suffrage parade on horseback in New York City to promote the enfranchisement of all women. In 1917, women finally acquired the right to vote in New York; Lee, unfortunately, she was not given this right since the Chinese Exclusion Acts were still in place.

Nevertheless, Lee did not give up and was determined to continue to advocate for Chinese-Americans. In 1926, she developed a community center in Chinatown intending to provide support and a feeling of freedom to those who were marginalized in American society. The center offered English classes, a medical clinic, and a kindergarten. She dedicated the remaining portion of her life to assisting Chinatown’s community.

Ultimately, Lee is a pivotal symbol of social change and perseverance for all women. Her dedication to suffrage and marginalized communities will be remembered for years to come.

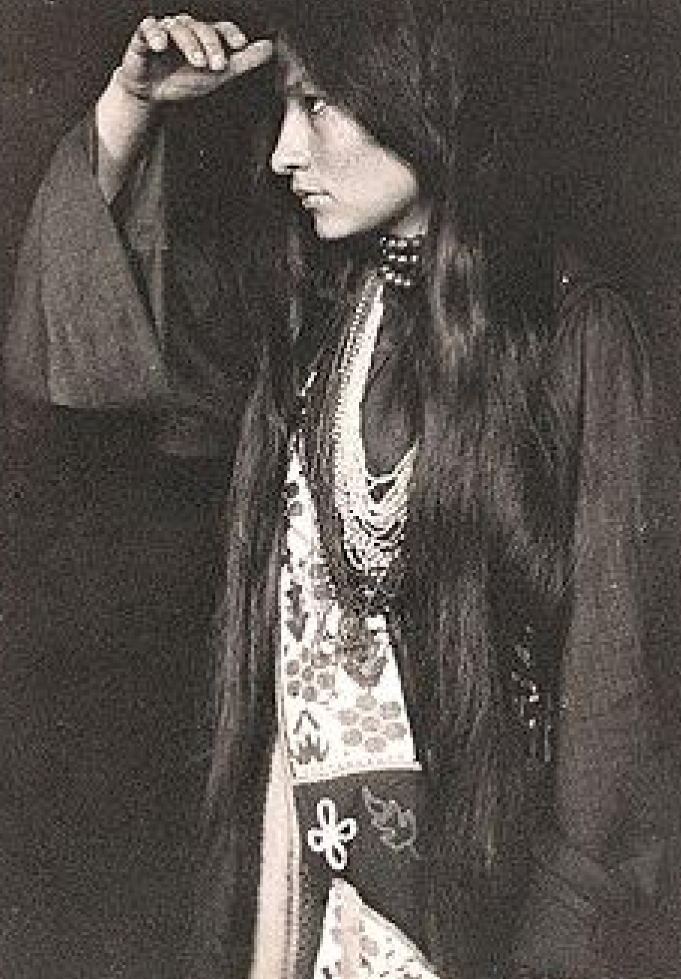

Zitkala-Sa

Contributed by Joanne Baptiste

Zitkala-Sa, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, was a musician, writer and activist who fought for Native Americans’ rights during the early years of the 20th century. At the age of eight, she was taken to a Quaker missionary school in Wabash, Indiana called the White’s Manual Labor Institute. It was there she was assigned the name, Gertrude Simmons, forced to cut her hair and pray as a Christian. She also learned to play the violin and piano, ultimately becoming a music teacher at the Institute. At age 19, against her parents’ wishes, she enrolled at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana where she began collecting Native American stories and translating them into Latin and English. After studying violin at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, she became a music teacher at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a boarding school for Native American children. She published short stories and essays in “The Atlantic” and “Harper’s” that portrayed Indigenous people without the racist stereotypes promoted by white American society. Her writings were very critical of the boarding school system. In 1901, she published an anthology of retold Dakota stories called The Old Indian Legends to preserve the traditional stories of her people.

In 1916 she became the secretary of the Society of American Indians which advocated for citizenship for Native people. She was vocal in her criticism of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ assimilationist policies and practice. She reported the abuse of children when they refused to pray as Christians. Her husband, who worked for the BIA, was fired that year. They moved to Washington, DC and she continued to work for the Society of American Indians, as editor of their journal. She traveled extensively and lectured about Indigenous citizenship and suffrage. Zitkala-Sa believed that Native Americans should be American citizens and should have the right to vote and be represented in government since they were the “original occupants of the land”. Although the federal Indian Citizenship Act granted US citizenship rights to all Native American’s in 1924, it didn’t guarantee the right to vote, that was left to the states. In 1926, she and her husband created the National Council of American Indians which supported universal suffrage. She continued to work for the Indigenous communities, influencing the Federal government to investigate exploitation of Native people and leading to the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. She died on January 26, 1928 and is buried with her husband at Arlington National Cemetery.

References

“Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird / Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/people/zitkala-sa.htm.

reports

Annual Meeting Reports

Our annual meeting reports include a full wrap up of each year. Our reports include Letter from the co-presidents, nominations, annual meeting financials, and so much more. Check out our annual reports, we make them just for you to easily digest information and understand the impact that we promise to make every year!

Major Event Reports (Journals)

Impact Report

Our impact reports are an easy way to get an understanding of all that we have done this year. We update our impact reports every six months to keep you up-to-date and in the loop with all of the current events and news.

the league in the news

September 12, 2025

Constitution conversation hosted by LWVNYC airs on BronxNet

As a special part of this year’s Constitution Day, the League of Women Voters of the City of New York and BronxNet Television hosted “What the Constitution Means to Me”, a lively conversation with Heidi Schreck & Ally Coll with community members and students from Hostos Community College of the City University of NY.

March 26, 2025

League of Women Voters hands out Tribute Awards

On March 25, 2025, the League of Women Voters of New York City honored Shaina Taub, creator of “Suffs” on Broadway, along with four other New Yorkers for their work in civic engagement.

Watch the video here.

February 28, 2025

NYC moves to protect domestic violence survivors by making their voter records confidential

A number of groups that aim to make voting more accessible for New Yorkers, like the League of Women Voters and the Center for Independence of the Disabled, also testified in support of the legislation.

“Extending voting protections for survivors is an important milestone for New York,” said Susie Gomes, chair of city affairs for the League of Women Voters, adding that the move would “bring awareness and education to this critical issue.”

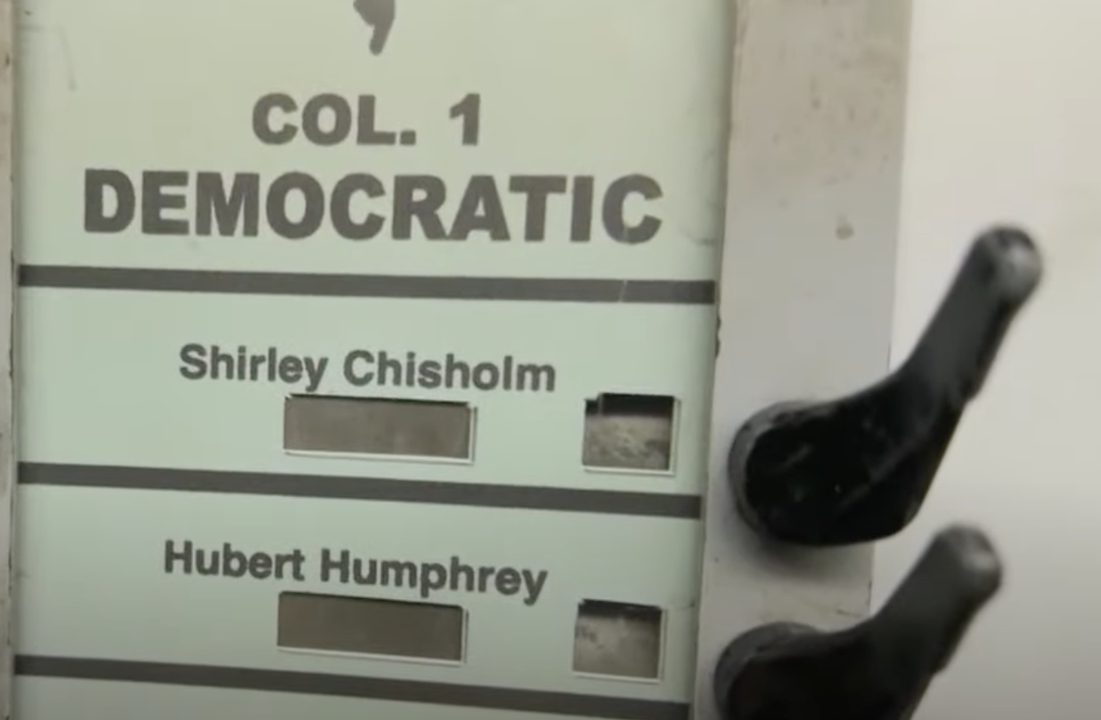

September 8, 2024

Brooklyn pays tribute to late, former congresswoman Shirley Chisholm ahead of her 100th birthday

“The one thing we have going for us is our vote, our one vote. And this is what Shirley is about,” said Karen Wharton of the League of Women Voters of NYC. “Shirley was about kicking down doors. She didn’t knock down doors. She kicked them down.”

Watch here

Brooklyn NY – Celebrating Shirley Chisholm at 100 Years

As stated by League of Women Voters NYC Board Member Karen Wharton, “Shirley Chisholm’s activism began, in part, at the LWVNYC, and her fearless leadership and advancement of democracy continue to inspire. That she was an African American woman of Caribbean heritage from Brooklyn blazing a political trail even before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 makes her a shero to me.”

Read more here

Celebrate 100 Years of Shirley Chisholm at Lefferts Historic House

The proud daughter of Barbadian and Guyanese immigrants and active member of the League of Women Voters, the Brooklyn NAACP and the Brooklyn Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc., Chisholm was a fierce proponent of the importance of voting.

Read more here

Organizations partner to celebrate 100 years of Shirley Chisholm in Prospect Park

Voter activation and registration will he held from 1:00 – 3 p.m., and performance and talk-back, 3 – 5 p.m.

Read more here

Organizations partner to celebrate 100 years of Shirley Chisholm in Prospect Park

The Prospect Park Alliance, in partnership with the League of Women Voters NYC, Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Brooklyn Alumnae Chapter, and Brooklyn NAACP, will on Sept. 7 commemorate 100 years of Shirley Chisholm.

Read more here

NYC museum exhibit honors Women’s Equality Day

Dave Carlins visits a pair of museum exhibits focused on women’s equality, a Broadway show celebrating suffrage and “get out the vote” efforts on the West Side.

Watch the video here

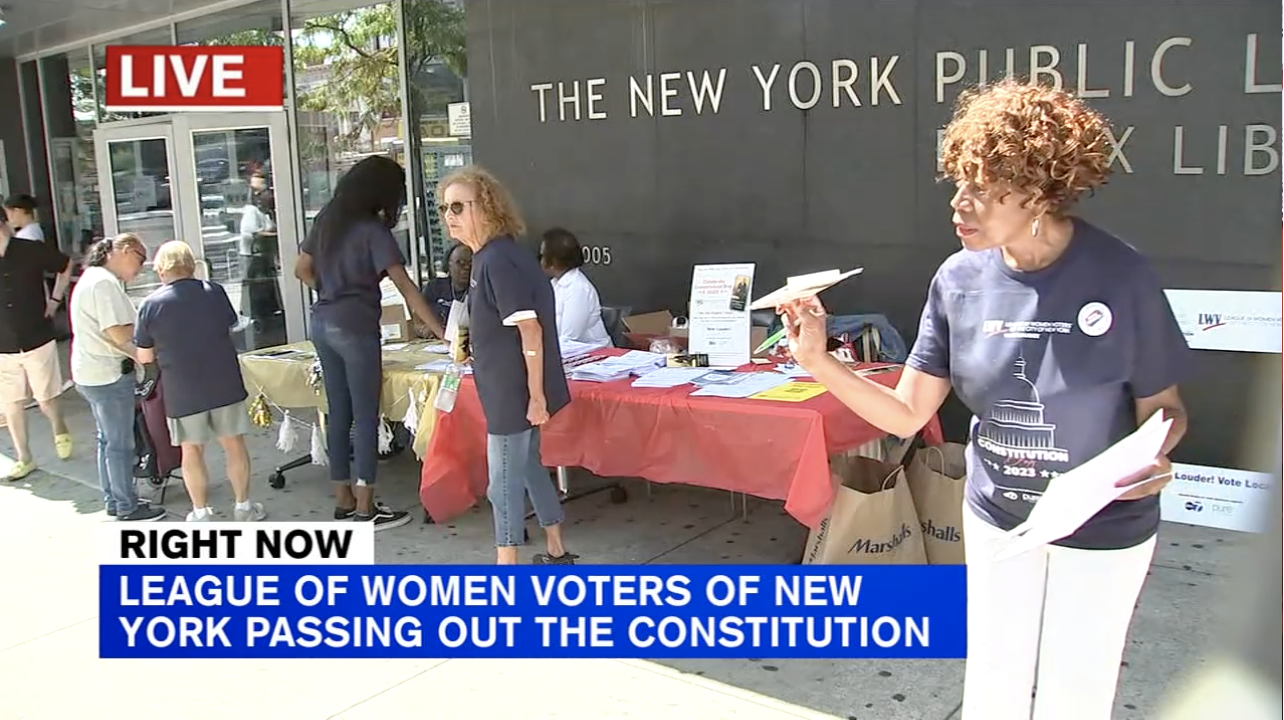

September 15, 2023

League of Women Voters of New York ring in U.S. Constitution Day in the Bronx

LWVNYC Board Member Patricia Manning speaks to the importance of registering to vote and voting local. Watch here!

September 12, 2023

Constitution Day 2023: Know your voting rights

Check out the video here explaining why the League commemorates this date, with volunteers handing out 10,000 free copies of the US Constitution in the week leading up to the official day!

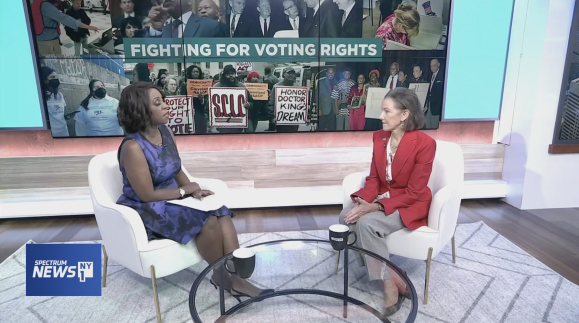

August 22, 2022

Kate Doran joins “In Focus” on NY1 to encourage voters to make their voices heard on important issues.

Check out the video here

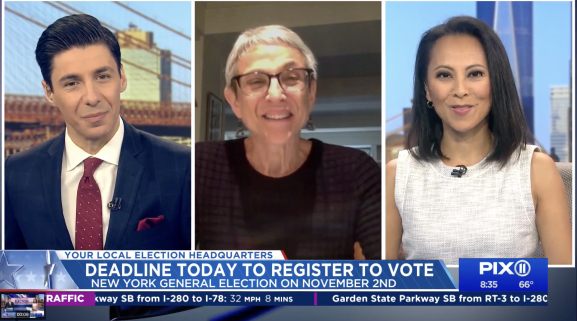

October 8, 2021

Diane Burrows appears on PIX11 Morning News to explain how New Yorkers can register to vote.

View the article and video here